Designing a service around the word “BLUE” at Global Service Jam 2019

Context

The Global Service Jam is the world’s biggest design focused innovation event, billing itself as “48 hours to change the world”. In 2019 the jam was held across a record 124 cities, including significant participation across China, South America and the the Middle East.

The purpose of the jam is to design a service based upon a design brief revealed on the first evening of the three day design sprint. This year the organizers simply shared the word “BLUE” in black type against a yellow background, giving participating teams free reign to interpret it as they wished.

Role

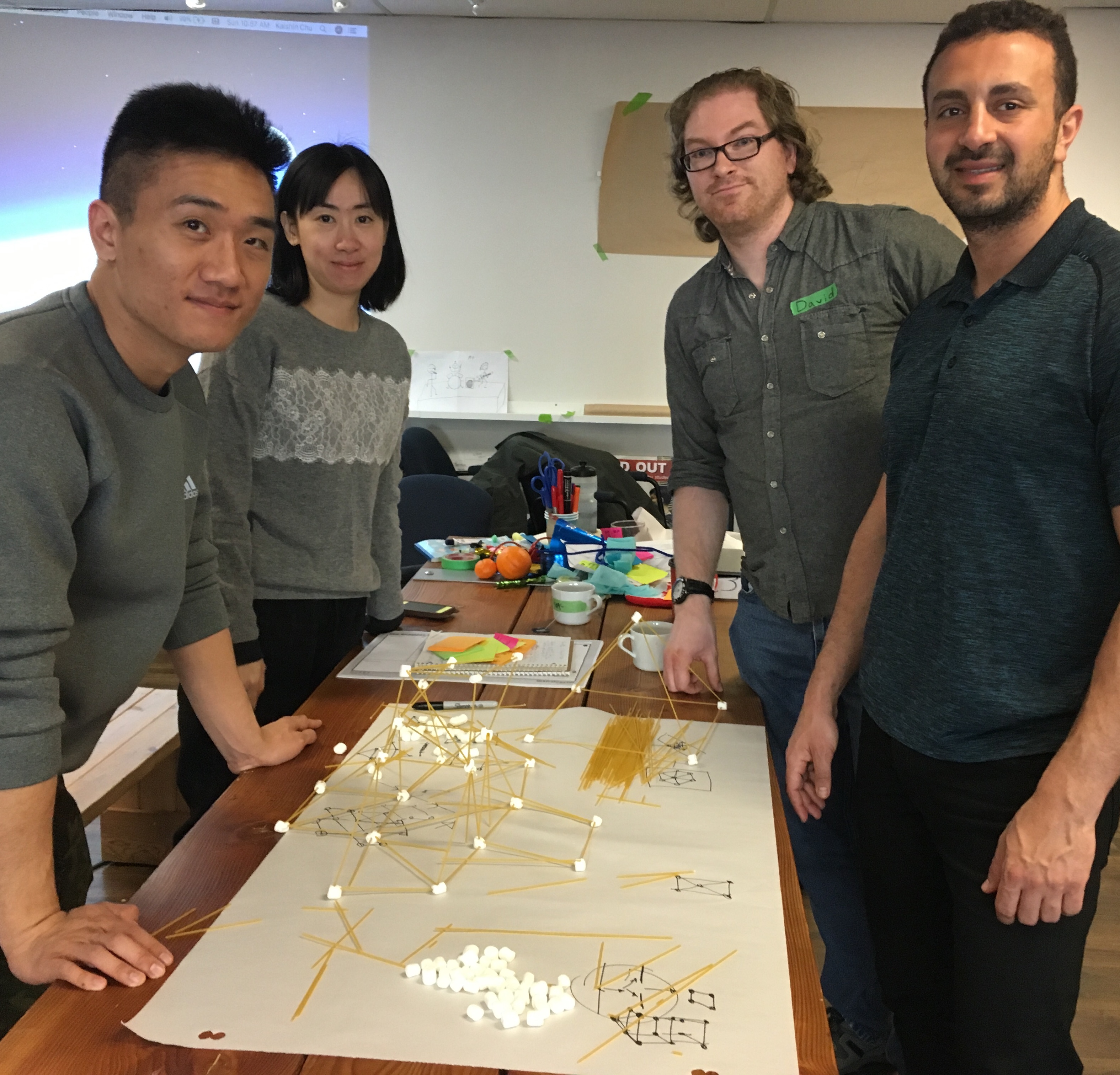

As a participant in my first ever Global Service Jam, I was fortunate to participate alongside a diverse group of professionals from around the world, including graphic designers and UX researchers to professors and sports professionals, each of whom brought a unique to the jam hosted in Vancouver, Canada.

I assumed a leadership role within my team, using my background in business development to help refine the business model and value proposition of several proposed ideas, as well as leading the prototyping process by developing storyboards and interviewing dozens of prospective users alongside Vancouver’s waterfront. By maintaining a curious mind and an energetic spirit, our team was able to gain deep insights which influenced the ultimate design of our “blue” service.

Process

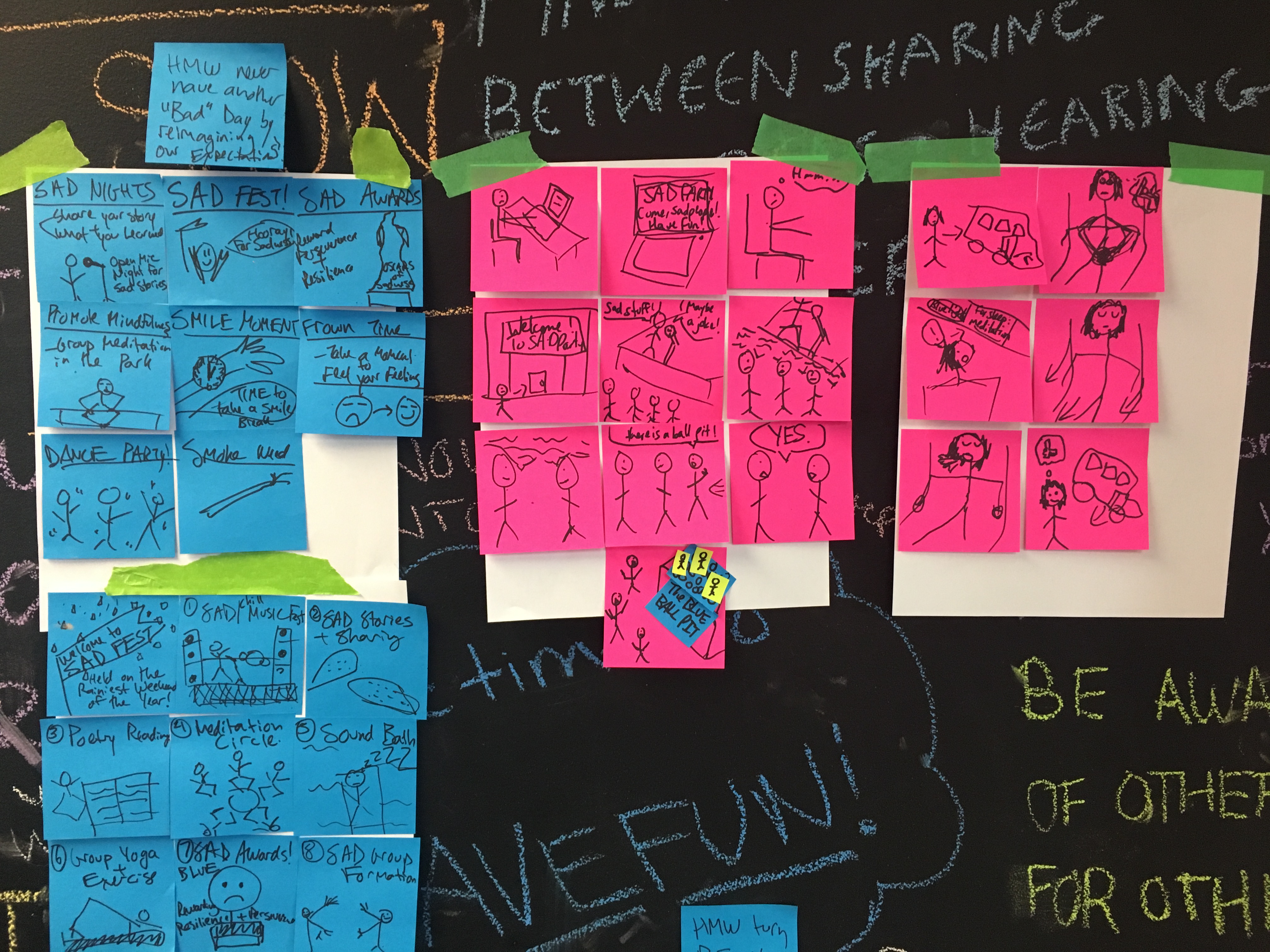

The process began with group members jotting down any ideas, words or sketches related to the word “Blue” on sticky notes which were later assembled by theme in the form of an affinity map. Several patterns emerged, including: feelings, the environment, conservation, products, fashion, and space exploration. After each member voted on the theme which resonated most with them we selected the area of “Blue” feelings, which we interpreted broadly as including curiosity, sadness, ambiguity, hope and possibility.

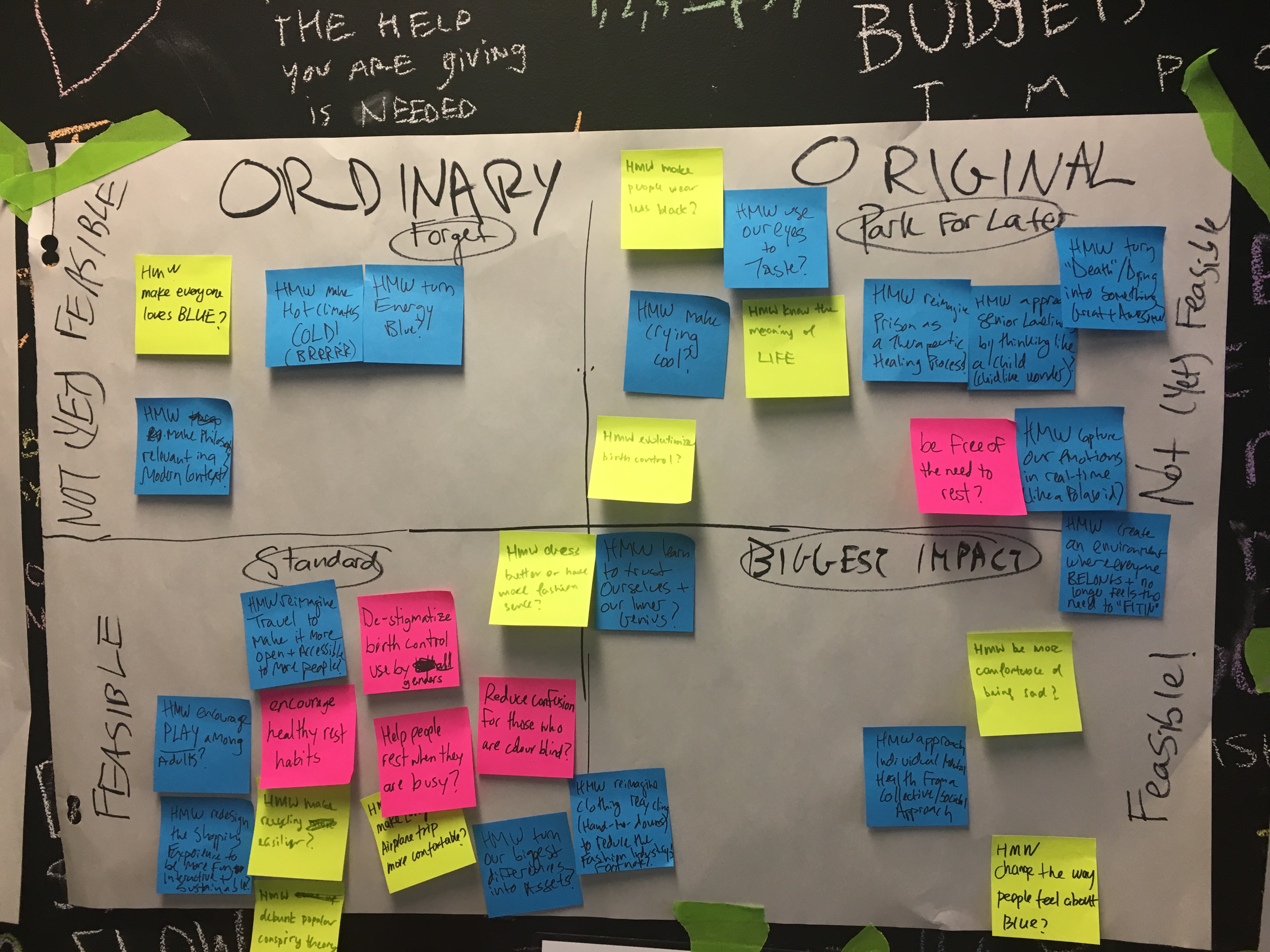

Once we’d agreed on a theme we ideated multiple “How Might We” statements, later categorizing them in a matrix based on their originality and feasibility. Statements deemed both original and feasible were considered to have the greatest potential impact as a service. As a result, we ended the first day of the jam by proposing the following statement: “How Might We persuade people that sad doesn’t have to be bad?”

The second day of the jam commenced by exploring the Empathize stage of the design thinking process by developing empathy maps which would inform our questions when prototyping two concepts we’d developed using storyboards for user testing.

The two concepts we tested included a weekend festival focused on removing the stigma around sadness and a service to track and analyze sleep and dream patterns, including a strong emphasis on developing a sense of community around the importance of rest.

The feedback from our user testing with local Vancouver residents revealed a majority interest in a single day event related to emotions, however, the idea of a “sad fest” was too narrow, with some users expressing that lingering stigmas related to sadness and depression might affect participation. Although elements of the sleep service storyboard appealed to some (primarily male) users, the bulk of respondents were skeptical regarding its practicality and their own abilities to commit to engaging in it regularly.

In Action

‘How Might We’ statements based on themes which emerged from our original ideation were categorized along a matrix to determine which ones merited further development. Statements deemed both original and feasible carry the greatest potential impact and would become prototypes for user testing.

Storyboards were developed for two ideas selected by our group to illustrate the user journey and features of each service. Once users were introduced to each concept, they were asked a series of open-ended questions to gauge their interest and solicit feedback to incorporate in subsequent iterations.

Our group engaged with a diverse selection of test users, including couples, students, retirees, and families, to understand which elements of each concept resonated with them and how the concepts could be adjusted to suit their needs and desires. Through research we were able to observe preferences based on gender and age, with younger women favoring the “Blue Fest” concept and older, wealthier men demonstrating interest in the ability to analyze their sleep patterns.

A physical mock-up of the mobile phone application allowed users to test its utility in terms of navigating the service offerings and guiding them through the physical layout of the festival.

By using toy characters and a 3D map we were able to observe the user journey, ask questions, and iterate several programming options to suit their individual tastes and desires.

Outcomes

Based on our user testing we developed several personas to capture common themes among the individuals we interviewed. As we incorporated user feedback into our service offering we decided to focus on the persona of a new university student acclimatizing to a different environment. As a result, the value proposition was adjusted to reflect a focus on addressing student needs in a familiar setting (university campus), while the business model was adapted to accommodate a student’s budget by including sponsorship opportunities. Our choice of communication channels was also updated to reflect a primary focus on social media (Instagram) as well as establishing partnerships with student groups and counselors.

User testing also revealed a strong interest over a single day event, rather than a weekend festival which required a greater mental commitment, therefore we scaled the programming to reflect this preference and introduced the use of “Blue Ambassadors” to guide attendees in an efficient manner so they can engage with minimal friction.

In developing physical prototypes for users to engage with we created a map of the festival, programming descriptions, email communication and a mobile application. We also used a physical stage and gallery space to allow users to explore the settings they would encounter as they interacted with the service. Finally, users were encouraged to voice their enjoyment or frustration with any aspect of the service, leading to some important insights around the value of different types of programming and obstacles to participation.

In reflecting on our Global Service Jam experience afterwards, our diverse group of participants observed how location affected our choice of service offerings, with each group targeting local users in designing services, which included a dog-walking service for residents of apartment buildings which don’t allow pets as well as a full-service event company designed primarily to provide options for young adults and families during rainy winter days.

In order to familiarize our fellow team members with our service, we invited them to walk through the concept to identify further areas for improvement. Our demo video was later uploaded to the Global Service Jam website and shared on Twitter alongside entries from around the world.